Looking Back with Love

She was born in Mill Valley in 1914—not in a hospital, of course, and not delivered by a doctor; that wasn’t the way things were done then, and perhaps it’s a good thing, because the town doctor at the time was also the town drunk. “If you went to get him, he might be off somewhere helping a cow give birth to cat” she says–not a reference to veterinary assistance he provided, but a comment on his general uselessness.

Instead, she was born in a cottage owned by the midwife who delivered her. When her mother’s due date approached, she packed a few things and moved in with the midwife until the birth. It was much more efficient than the midwife having to traipse all over town whenever an expectant mother needed her.

Mill Valley now is barely recognizable as the town in which Maxine Palazzi grew up. The city is much bigger——not the speck of a town where everybody knew everyone else. There are no longer trains carrying home commuters fresh off the Sausalito ferry. And the name of the street she grew up on has been changed. Once it was Laurel Avenue. Now it’s Laurelwood.

“Can you imagine?” asks Palazzi. She left Mill Valley three-quarters of a century ago, but her memories of the city are vibrant and tender. It was an innocent time, both in the century and in her life, and she smiles whenever she says “Mill Valley.”

To Palazzi, Mill Valley in the early '20s was a place where children strapped roller skates onto their shoes on warm Saturdays, skated down to Tam High, and paid 25 cents to swim. “Then we’d skate all the way home!” she exclaims. If she and her friends were thirsty, they’d stop off at her aunt Floy’s house on the way home.

“My aunt made root beer,” she recalls. “I was always going in to taste it. She didn’t have a cellar [for brewing], she had a dark closet. And she always had a barrel of pickles she was making in there, too; she made the best pickles. It was such a wonderful time. This was right across from the old mill, and then we’d go across and jump on the old ties. Oh, I loved [the town]. I knew every little nook.”

The center of her world back then was her father, Charles Palazzi. He was the butcher for the now-defunct Tamalpais Market, on Corte Madera Avenue, and to Palazzi he was like Superman—although the world wouldn’t hear about Superman for another couple of decades. “He did everything!” she exclaims. The trains coming in from San Francisco would be so crowded with visitors on weekends that “he gave his time as a ticket collector on Sundays. He was a policemen during the week. He was a fireman. When the bells started ringing, he’d [leave the butcher shop]. If the fire truck went by, my father would take off his apron and be in time to catch the bar to get on the last step of the fire truck.”

And he didn’t stop with fighting fires; Charlie, larger than life to his daughter, would take on any kind of emergency that cropped up-perhaps most memorably the time a bear was loose in downtown Mill Valley. The bear was belonged to a local man who had a private menagerie on Mt. Tam, and Palazzi didn’t want to shoot the bear. But he was leery of approaching it, especially of being grabbed in a powerful “bear hug” and being unable to free himself. But the creature didn’t seem inclined to go home, and was too dangerous to leave, so Palazzi had to approach him. The bear, as feared, grabbed him and was squeezing for all he was worth before some other men finally stepped in to pull him off. His owner, a well-known eccentric, finally came down off the mountain and took the subdued bear home.

Her mother, Merle McArtor Palazzi, was a decided contrast to Charlie Palazzi. Charlie was a gentle Italian whose family had arrived in Mill Valley at turn of the century. Merle was a stern, lovely transplant from Washington state who was a tiger in an age when women had yet to receive the vote. When the time came for them to be married, she declined to convert to Catholicism to please her new husband and his family, so instead of being married at the altar of the church, they were married in the priest’s house. And when Charlie was late to dinner, Merle thought nothing of marching out of the house, renting a buggy, and driving out to demand he return posthaste.

Charlie, on the other hand, was a soft touch. One day a frantic search for young Max concluded when her father found her near the town cemetery with a friend, who had suggested the trip in the hopes of seeing “something open.” All the way home Charlie lectured his daughter, and then announced to his wife, “There’s no need to correct the child, I corrected her on the way home”—which didn’t prevent Max from getting a swat from her skeptical mother.

Palazzi took a special joy in car trips, when she was allowed to sit in the front between her parents, her younger sister Bonnie alone in the back. “We had a Model T Ford … and I could turn off the key. We’d coast down hills to save gasoline; oh, I thought that was terrific! He’d let me turn off the key and go whizzing down.”

A typical family trip might be to Sonoma—a route with lots of hills, and therefore many coasting opportunities—or to Big Lagoon at Muir Beach, a special favorite with the local Italian population.

On the beach at Big Lagoon was a little house. “It was one big room, and they had a phonograph inside, so the hikers could come in [and dance]-the people from San Francisco would come in on the boat and get off the electric train at the Alto or the other stops and then hike to Muir Woods and Mt. Tamalpais and Big Lagoon—there was always trainloads of people.” On the beach, children and adults frolicked in hats and heavy woolen swimsuits that covered most of their bodies.

“My father and his friend Johnny Bucalotti would dig mussels and clams and make cioppino on the beach,” recalls Palazzi fondly, who enjoyed the rare sight of her austere mother, relaxed by the sea breezes, cutting up with her sister Floy. “They liked to get all of those things—mussels, clams, eels—all that kind of awful stuff. All the Italians, the old bucks, they’d all meet there, and come for cioppino.”

If the leisure time was spent with family, the working hours for the older Palazzis were spent with … even more family. The Tamalpais Market where Charlie Palazzi worked was owned by Charles Cervelli, who was married to Palazzi’s older sister, Susie. Adjacent to the butcher shop area was a delicatessen and grocery store; Max’s mother worked in the delicatessen. “My mother ran the delicatessen and made all the salads and cooked lunch for all the men who worked there,” says Palazzi.

Charlie’s mother, Rose Palazzi, also worked in the delicatessen. Rose Palazzi had set out from Italy with her husband Joseph and their daughter Susie while pregnant with Charlie, given birth during a stopover in Alsace-Lorraine, and then continued on the journey to Mill Valley. In a room in the store in which no one was allowed but her, she made ravioli, rolling them out on sheets on the floor. “It was the ravioli room,” Palazzi says simply. Her grandmother would let her stand in the doorway to watch the patient process. Some evenings Max and her father would visit Rose, who lived a few doors down from them on Laurel, and Rose would make them zabaglione, which infuriated her daughter-in-law-since zabaglione, an Italian custard served warm, contained wine. She didn’t want her young daughter eating something made with wine, but her earthier mother-in-law couldn’t understand her objection.

Of course, it was also illegal, Prohibition being in effect. But needing it for many beloved dishes, and being practical, Charlie Palazzi made wine for the family in the barn behind his mother’s house. It did the job, even if it did taste of the foot.

The cozy working relationships of the family—almost every position in the butcher shop and grocery store/delicatessen was filled by a Palazzi or a Cervelli—ended abruptly with a lunchtime disagreement between Merle and Irene Cervelli, Charles Cervelli’s daughter and Charlie Palazzi’s niece. Max, being only 10 years old at the time, was not told what the argument was about, but it was serious enough that Charlie removed his apron and escorted his wife and his mother from the store. None of them would ever work there again.

It wasn’t difficult for him to get another job. Andrew Webber, a Sausalito businessman, was opening up a butcher shop there and hired Charlie within a few days of him leaving the Tamalpais Market. Charlie was popular with customers in Mill Valley, says Palazzi, because he kept the shop open until all the commuters returning from San Francisco had arrived and gotten meat for their dinner. The habit irritated his wife, since her own family’s meal was delayed, but his customers appreciated it.

Death somehow seemed a more substantial presence in those days—something that was always present. Of course, it’s still present, but not many people today have sat on the bedside of a friend, playing checkers, only to have her expire of the flu two days later, as Max Palazzi did during the Spanish influenza outbreak at the end of World War I. And people today are seldom whisked away from their families and confined because of diphtheria, as her mother was.

The Marin flood of February 1925 was powerful, destructive. The San Francisco Examiner devoted a page to dramatic photos of the flood in Mill Valley alone. “Heavy flood damage from torrential rains in Bay district,” reads the headline; local historian Lucretia Little later wrote that “giant redwood trees moved upright in a sea of mud down the canyon from Marin Avenue to Cascade Drive, a block west of the Old Mill.” The Arroyo Corte Madera del Presidio Creek that cut through Rose Palazzi’s back yard swelled with the flood, and the bulkheads were loosened. It wasn’t until June 28 that Charlie had a chance to repair the damage. He and his good friend Bucalotti went to work on it together, and the thought of the two of them makes Palazzi smile. “My dad was almost six feet, and Johnny was about five feet; they looked like Mutt and Jeff,” she laughs.

Palazzi remembers the day clearly. “My father had these big ties, and was handing them down to Johnny in the creek bed. My father was above, and he was driving the big spikes into them and handing them to Johnny to create a bulkhead,” says Palazzi. “We had a Model T Ford, and we were going to Sonoma. My mother had called me to go to the store, and I didn’t want to go. My father said, ‘Bummy –’ he always called me Bummy because I was always bumming after him—so he said, ‘Bummy, go and get your mother whatever she needs. And then when you get back we’ll go up to Sonoma.’” As she ran to the store, she passed by a carnival that was in town that day, and heard the popular Irving Berlin song “Blue Skies” playing as she went on her way.

When Palazzi came home from the store she found her father in the house, stretched out on the bed. As he had handed a tie down to his friend, the spike had caught in the cuff of his trousers and jerked him down the eight-foot incline. His head cracked against a rock as he landed.

The doctor was sent for, but as was usual, he was useless. “He was passed out,” says Palazzi flatly. “He couldn’t even stand on his feet, he couldn’t do anything.” In desperation a doctor for sent for from Kentfield, the same place Merle Palazzi was once confined due to diphtheria. He didn’t arrive in time. Charlie only lasted three hours. He was 33.

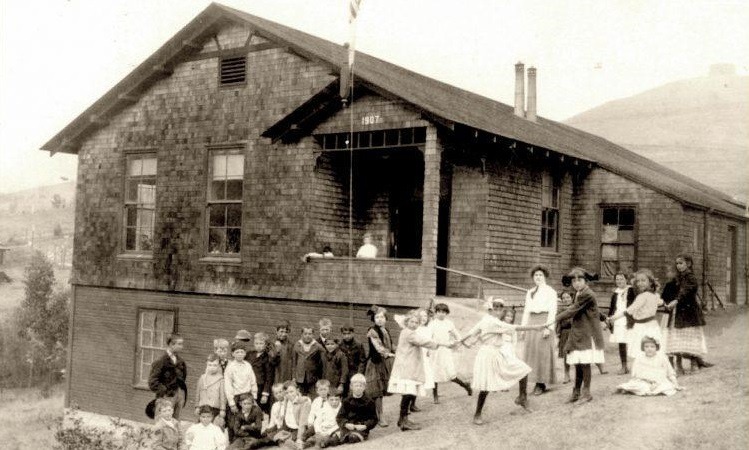

It was an unimaginable end to a childhood that had been filled with joy. The person she loved most was dead. A year later her mother remarried and the family moved to San Francisco. Palazzi left Old Mill School, which she had been so delighted to attend; then, it was the new school in town. She left her adored cousin Marvin Cervelli, only two weeks younger her junior and her best friend from the time they were babies. She left her home, and all the places imprinted with her father’s memory.

“Oh, how I loved that Mill Valley,” she says wistfully. “My aunt said, ‘Max, you come over whenever you want. This will always be your home.’

“And it was true.”

----

Originally published in the Mill Valley Herald.

Post a comment